When we were very young

While I was buried in old memories and news archives writing my uncle's obituary, my son asked a vulnerable question. I gave him a kid-size answer. This is the whole one.

“Mom, why do you think I’ve been getting this weird feeling?” my 9-year-old son asked one recent evening.

For the past few weeks he’s had trouble falling asleep. He comes into our room for extra hugs, sometimes two or three times, asking if we “heard that noise.” I probe a little further.

“Is the feeling in your body, or just your mind, or both?”

“My mind, I guess. But sometimes I feel like I can’t catch my breath.”

“What you’re describing sounds a lot like anxiety. Is there something you’re worried about?”

“I’m just scared someone’s going to break in, like a serial killer or something. I don’t even know what I’m supposed to do. Would I try to be quiet, or should I fight?”

Don’t ever let someone take you in a car with them. If someone tells you ‘your mommy or your daddy sent me,’ you ask them for the password. If they don’t know it, you run.

“Well, first of all, nothing like that is going to happen. We live in a safe neighborhood. We have cameras at the doors. Our house is small, and Dad and I are right across the hall. But if it makes you feel better, if anyone ever tried to grab you or harm you, you yell out and kick and punch and we’d be there in seconds.”

You bite, you kick, you punch, you yell ‘I don’t know this person! I don’t know this person! ‘ And you don’t stop until someone helps you.

“And if you were in public, you kick and punch and bite and scream out ‘I don’t know this person! I don’t know this person!’ over and over, so people wouldn’t think you were just a kid misbehaving with a parent.”

“Okay,” he said.

I glanced down the street as I crossed, tightening my grip on the sharpened pencil in my hand. I ran.

“But lots of kids feel these kinds of fears, especially sensitive kids. Dad felt anxious at night sometimes, and so did I. But just remember: our neighborhood is safe, our house is safe.”

What I didn’t tell him was that although lots of kids have fears of killers and bad people breaking into their homes, mine were not unfounded.

The first place I remember living was my grandparents’ house on Marbella Avenue. I was five years old. My parents and I had just immigrated back to Los Angeles from Northern Ireland, my mom’s home, and we stayed with my dad’s family while they looked for an apartment.

A decorative breeze-block wall shielded my grandparents’ front patio from the street. They had an extra, small living space at the center of the house containing the piano, Papa’s desk, and a hide-a-bed sofa where my parents slept, where eventually I would sleep when I stayed over. Against one wall in that room, a bookcase held treasures from Papa’s time in the Navy, textbooks from Paca’s later-in-life nursing training, and my favorite: two volumes of children’s poetry by A.A. Milne, at just the proper height for me to reach.

They're changing guard at Buckingham Palace

Christopher Robin went down with Alice.

Alice is marrying one of the guard.

"A soldier's life is terrible hard,"

Says Alice.Tall arborvitae lined the concrete wall behind their house, shielding their property from the chemical plant on the other side. Our side of the wall, though, was a little oasis. A patio with pergola providing shade, lined with concrete planters every few feet. A knee-height retaining wall I could balance on that separated the grass from the concrete.

My first birthday party was in that backyard. We had Easter egg hunts there, rifling through the tropical perennials for prizes. Papa would follow my little brother around as he led them from one adventure to another on the little parcel of land on Marbella Street.

“Paca wants to know if you’ll do a nice write up for Uncle Randy, like you did for Papa,” my dad texted me the day after my uncle died. My first job out of college was as the Celebrations Editor for the local newspaper. But over the years my family has repeatedly asked me to apply my skill-set to a more somber task: I’m the designated obituary writer.

First was my mother-in-law, Debbie. She quietly breathed her last just after sunrise, at peace in the arms of her family.

Then my Nanny. A lover of children, a World War II veteran, an expert knitter, generous to a fault.

Papa. Jim was a man of great faith, integrity, and devotion to his family.

Now, Uncle Randy.

“She’d like you to talk about the wheelchair race he organized at El Camino. She said an L.A. County Commissioner attended and the Daily Breeze covered it.”

“Sure,” I replied.

For wedding and engagement and anniversary announcements, the newspaper had a formula. I’d gather all the specifics, perhaps correspond with the bride or, god forbid, the mother of the bride, about any special details they’d like to include. But for obituaries, if you do them well, there is no formula. You give the name of the deceased, of course, and likely the date of their death. But what comes next? How do you encapsulate a life in a few paragraphs? How do you honor the dead, and comfort their survivors, and tell the truth all at the same time?

Looking through old photos of Uncle Randy, so many were taken at the house in Carson. Of my immediate family, only eight of us are in the United States. Well. Now we are five. When I was five, I was just alive. But now I am six, I’m as clever as clever. I think I shall stay six forever and ever. But back then, we were eight, and we all lived in Los Angeles, and we alternated holidays between my parents’ home and my grandparents’ house on Marbella.

“Do you guys remember the issue with the factory by Paca and Papa’s house?” I texted my mom and dad while I searched the archives of the Daily Breeze and the El Camino Warwhoop, gathering articles about Uncle Randy’s election to the school senate, his activism for the disabled community.

“I remember they eventually got a payout for something a while ago, but I don’t remember what,” my mom replied.

I veer slightly off track, pulled by the lure of the photos, the wisp of a memory of some problem with the factory behind their house. I enter new search terms: Carson neighborhood, factory, lawsuit.

Toxic soil lurks beneath Carson neighborhood

LA Times, April 27, 2010

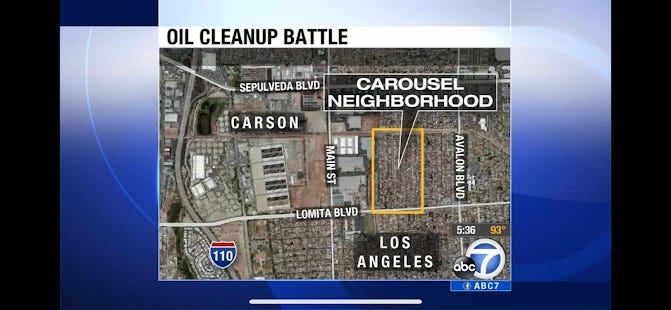

Preliminary tests under the direction of the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board had found dangerous levels of potentially explosive methane gas and benzene under the 285 homes of the Carousel tract. In some spots, tests found benzene at concentrations seldom seen, levels that could significantly increase cancer risks for residents.

The discovery has transformed a 50-acre neighborhood of palm trees and quiet streets into…

Work begins on massive cleanup of contaminated Carousel tract yards in Carson

Torrance Daily Breeze, May 13, 2016

Beginning a five-year clean-up process across the 50-acre community, workers ripped out carefully manicured plants and lawns and dug up trees.

Like all families in the neighborhood of 285 homes, the Anchetas were told nearly a decade ago that the soil beneath and around their homes was full of toxic petroleum waste. They were warned not to plant vegetables or let their children and pets dig in the yards off Lomita Boulevard and Neptune Avenue, and then — counter-intuitively — assured their health wasn’t in danger from the petroleum hydrocarbons. Many residents suspect the pollution has triggered…

“You guys aren’t going to believe this,” I texted my parents.

New information, truths revealed some ten years after my grandparents retired to Albuquerque, that I’m only just now learning. Not what I expected to find after typing their old address into Google Earth. I was disappointed to see the decorative wall has been removed. But images of the neighborhood entrance, those were shocking.

Sometime in the 60s, unwitting developers purchased a tract of land from Shell Oil and constructed a neighborhood of 285 homes. My grandparents bought one of them.

The house where I ate Little Ceasar’s and Dreyer’s ice cream on special Saturday evenings—one scoop of chocolate and one of vanilla; where I had birthday parties; watched Papa tend to a litter of kittens a feral cat birthed behind a planter; where Paca taught me to play piano and sing: that house sits on soil saturated with more than a hundred thousand times the legal amount of benzene.

My grandfather lived to be an old man, but he had prostate cancer while in that house, and he died of metastatic bladder cancer.

What else am I missing?

From my grandparents’ house on Marbella, we moved into an upstairs apartment in a duplex in San Pedro. I have warm memories of Christmas there, and my little brother zipping around the tiny living space on a tricycle. I also remember lying in bed while a deep bass beat thrummed from the alley below: the soundtrack of drive-through drug deals. Once, on an after-school walk to the beach, a man lay unconscious on the street in front of us. His legs were in the gutter, his torso and head on the sidewalk. We moved again not long after that.

Our next house was a rental off Crenshaw Boulevard; there was only one house between ours and the chain-link fence that separated the 405 freeway from our street. Google Earth shows the house that was tan is now a pale, sage green. A decorative iron safety gate covers the front door.

I didn’t know then, being a child and all, but several different series of murders occurred along the L.A. freeways in the 70s and 80s. With my friends April and Aubria I discovered a portion of the fence had been cut and peeled back. Alma and Don from across the street warned my parents of a prowler in the area. This was the early 90s; my dad had wanted to buy a gun. My mother wouldn’t let him.

Another memory. I text my mom.

As I downloaded article after article that mentioned my uncle and his senate races at El Camino, searched the archives of the Daily Breeze and LA Times for information about the toxic Carousel, I was drawn into the current headlines.

4 handguns found in San Pedro’s Peck Park after weekend shooting killed 2, injured 6

Off-duty LA County sheriff’s deputy shot in dispute in Harbor City; 1 in custody

California’s ongoing K-12 student exodus

6th Street Viaduct reopens after LAPD shut it down for the fourth time in five days

How a skid row store faces the tensions in Black-Korean history — by discussing its bleakest chapters

I click on that last one.

The story of why the everything store tries to do so many things has a lot to do with Danny, but it really started long before, on a Saturday morning in 1991, when Korean American shopkeeper Soon Ja Du fatally shot Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl, at a South Los Angeles liquor store. …

Danny was a kid then. Now 38, he knows that no matter his intentions, someone will see the store as just another Korean American business profiting from a mostly impoverished Black clientele.

So another thing he wants the store to do is remember that history. Danny keeps a framed photo of Latasha at the front and a printout in his office, taped at eye level when he sits at his desk.

Even if it hurts, even if you’re ashamed, Danny said, you have to keep the images close, because “that’s how we heal. Because by remembering, that’s how we learn.”

I felt safe enough in elementary school; this was the era before mass shootings. My classmates and I were too young to absorb and identify with the turmoil swirling outside the high fences and locked gates surrounding our school. We were just friends. We were neighbors.

I’d heard the name Rodney King, and I knew there was some big trial going on. Between memorizing times-tables and learning to spell conservation (don’t waste water!), we added riot drills alongside the earthquake drills. For earthquakes we had to crouch under our desks and cover our heads, but for riots we had to stuff a towel under the door, draw the vinyl curtains, turn off the lights, and sit with our backs along the far wall away from the windows. We did those drills in 1992, while just 8 miles away, the intersection of Florence and Normandie burned.

Can we—can we get along? the aggrieved Rodney King stammered on TV two days after Reginald Denny had his skull stoved in with a cinder block, as the riots and looting raged on. Can we, can we get along? Can we stop making it horrible for the older people and the kids?

Crenshaw was the western border of the curfew zone; our house was to the east of it. But our neighborhood was a couple miles from the southern border of the zone, at Century. Not so close we were caught in it. Close enough to worry.

We did the riot drills again in 1995, leading up to the O.J. Simpson verdict. But there were no riots then.

I mean, please, we can, we can get along here. We all can get along. We just gotta. We gotta. I mean, we're all stuck here for a while. Let's, you know, let's try to work it out.

In a surprise twist that stunned my loved ones and upended everything they knew to be true about me, I recently started watching true crime shows. I wouldn’t normally subject myself to true crime; my mind is a carefully curated storehouse where redemptive works get the spotlight and the unsavory, loathsome, or troubling pieces–such as ghost stories and horror movies–get locked in a box and shelved in permanent storage. But it’s been a rough few months. The death of my uncle, major health problems with close extended family members, the death of a neighbor. My TV preferences have matched my dark mood.

The Innocence Files. The Staircase—both the documentary and the HBO series. Black Bird. The docuseries I Am a Killer achieves a uniquely fascinating angle: all the interviewees admit to being guilty of their crimes. Many of them are or were on death row. Most of them, I pity. A few of them I actually believe have changed substantially, substantively, since their incarceration.

All those old newspaper articles I dug up, the memories swirling, catalyzed by the disconcerting true crime stories I’ve been consuming, all of it led me to do something I almost never do: I went to that personal archive in my mind, and I opened a drawer.

I think I might know of someone on death row.

On Monday, May 10, 1993, the mood at my school was subdued. Something bad had happened over the weekend. Something really bad had happened in a house just a block away, at the home of one of the students. A boy named G. He was a couple years younger than me; I didn’t know him. At the time, I was 9 years old.

That Wednesday evening at church, I overheard Mrs. C tell my parents more. She also lived on 180th, on the street where the crime had taken place. A woman had been badly hurt. A man was murdered. There had been a baby in the house. Mrs. C had two teenage daughters; sometimes they left their door open on hot days, with only the screen door as a barrier. Not anymore.

All I knew for sure was this horrific crime had turned 180th into another distressing landmark on my route home.

Don’t ever let someone take you in a car with them. If someone tells you ‘your mommy or your daddy sent me,’ you ask them for the password. If they don’t know it, you run, my mom had instructed me. She’d let me choose the password.

After the end-of-school bell at 3:10, I’d sling my backpack over my shoulder and exit the front gate onto Yukon Avenue. I’d cross the parking lot and head south. The first hurdle was the underpass: the 405 freeway angled over Yukon, casting a deep shadow. A chain-link fence separated the sidewalk from the street: a dark, narrow gauntlet of dirty steel and traffic to one side, a concrete wall on the other. Once, I got caught up between rival gang members flashing signs at each other. I squeezed past them against the wall and took off.

Keep a sharpened pencil in your hand, Nanny told me. And if somebody tries to grab you, you use it.

North Torrance High School was the second hurdle. On the corner of Yukon and 182nd, loitering teens were always going to feel intimidating to a little elementary school kid. Nobody ever gave me any trouble, though one year teachers warned us not to accept any stickers or candy from the high schoolers. Rumors of them surreptitiously giving little kids drugs, I guess, though I never knew of any. I would’ve attended North, if we’d stayed in L.A. Chuck Norris graduated from North; then again, so did the Freeway Killer—the first California inmate to be executed by lethal injection.

Next I skirted another, smaller underpass, this one far less menacing, located on a drab, curved section of 182nd where one morning a swarm of roly-polys caught my attention long enough to make me late for school.

Then it was smooth sailing to my house on Delia. I passed by my friend C.’s abuelo’s street, at which point I knew I was home free. Nanny would be there, and my little brother. A snack and some cartoons, maybe riding some bikes or playing baby dolls with April, or finding her pet tortoise in the backyard, or maybe having a G.I. Joes battle with Aubria, then playing baseball in the backyard when dad got home until dinnertime.

At night, I’d watch the shiny black and white tiger barbs dart around the fish tank next to my bed. Their busy little lives unfolding in the microcosm-within-microcosm of my childhood room.

I had a wonderful childhood, because I had a stable, safe, loving family and a small, tight-knit church community. My Irish grandmother lived with us. I saw my grandparents and uncle at least twice a week at Coastline, a modular-building-of-worship located between a mechanic shop and a trailer park where my mom’s boss lived, an elderly man with a small transcription business who paid me to stuff envelopes with fliers he’d mail to potential clients. I was held safe in the warmth of so many adults who cared about me.

But I was also surrounded by other kids who didn’t have any of that, and the fact became more noticeable the older I got.

There was D., whose father was absent, who struggled with making good choices, who would come to Wednesday night Bible study and cry, a chain wallet and undercut hair belying his sensitivity and cavernous pain. There was A., whose single father became quadriplegic in a biking accident, his nose sheared from his face. T., who was chronically unsupervised, a slow moving train wreck of ever worsening behaviors. There were the kids in middle school who smoked pot on the playground; one of them was arrested for some unspecified misdemeanor when her own mom called the cops. There was C., whose dad was much older; she called me crying one afternoon to tell me he had died of a heart attack.

And of course there was Jose, subject of the very first obituary I ever wrote, for the school newspaper. He sat in front of me for gym class roll call—his last name began with S, mine with T. He was the only kid in class who was shorter than me, who couldn’t keep up with the pack when we had to run laps. He died of AIDS in 7th grade.

And there was L., my best friend since infancy, who didn’t have a relationship with her real dad. We—L., me, and her little sisters—would cram into the tiny backseat of her mom’s hatchback and beg her for Taco Bell. “…Okay,” she’d sigh, exhausted, and from the meager amount of money she earned cleaning houses she’d order us a 10-pack of crunchy tacos that we’d eat at the kitchen counter in her great aunt’s house, where they lived for a while. Once, L. and I were playing in a little neglected sandbox outside her apartment when her stepdad and a man from the building next door started arguing, yelling from stoop to stoop while we played between them. Her stepdad brought out a taser and threatened the other guy. I remember my heart racing and that neither of them were wearing shirts.

Maybe these impressions are blown up caricatures of what really happened, I thought as I waded through the memories, searching the newspaper archives. They’re bigger in my mind, the way buildings you saw in childhood turn out to be so much smaller when you revisit them as an adult. Because there was also Annette, Christian, Helen, Alison, Josh, Taka, Marissa, Nathan, Sarah and so many others who were normal kids, remarkable in their unremarkability, just like me. I’m even friends with some of them on Facebook now. Annette is happily married and still lives in L.A. Christian works for a set construction company and recently played steel drums for a legendary local L.A. workman musician. My childhood best friend L., well she’s been sober and happily married for years, with a great house overlooking Morro Bay. She has a wonderful, talented son. She and her husband own and operate a family-friendly recreation business, and she runs a t-shirt business on the side. In fact, I’m wearing an RBG t-shirt I bought from her.

And yet. Three months ago, L.’s stepdad was found dead in his trailer: an overdose. I’m sorry, L., I texted her. It is just shitty all around, she replied. I scrolled through the photos L.’s sisters posted on Facebook of their small ceremony at their dad’s interment. They are beautiful women, with beautiful children.

On May 9, 1993, 22-year-old Randy Garcia broke into a home on 180th Street, tied up Lynn Finzel, and repeatedly assaulted her while her baby slept nearby. When Lynn’s husband Joseph Finzel returned home, Garcia shot him, then shot Lynn as well. While Garcia rifled through the house for the next two hours, Lynn Finzel played dead. Pressing against her wounds to stanch the flow of blood, she struggled not to drown in the punctured waterbed where she was bound. Eventually Garcia left, taking only some jewelry and items from Joseph’s pockets. In the wee hours of the morning, Lynn stumbled to a neighbor’s house for help. Joe lay dead in their bedroom, their daughter’s bassinet between his feet. A few days later, Garcia was arrested in Oregon. He was wearing Joe Finzel’s wedding ring.

Jury Urges Execution in Murder, Assault : Courts: Victim’s widow, who survived being shot, hugs panelists. Verdict was returned after six-day deadlock

LA Times, Jan. 28, 1995

The jurors delivered their verdict after six days of what several of them described as grueling deliberations. During that period, the jury foreman twice told Judge Jacqueline A. Connor the panel was deadlocked. But Connor ordered them to continue meeting.

The final holdout against the death sentence changed her mind Thursday night, other jurors said. The juror was not identified.

TORRANCE: Man gets death in murder of rape victim’s husband

LA Times, March 24, 1995

“You don’t want the death penalty,” Lynn Finzel said in addressing Garcia during the defendant’s lengthy sentencing hearing. “Joe and I didn’t want death. We had no judge, no jury. You decided to be the judge and jury.”

Court upholds Death Row inmate’s sentence in Torrance slaying

Daily Breeze, Sept. 6, 2017

The California Supreme Court on Thursday unanimously upheld an Oregon man’s conviction and death sentence for murdering a father of two and sexually assaulting and trying to kill the man’s wife during a home-invasion robbery in Torrance nearly two decades ago.

Above the album of L. and her sisters at their father’s memorial, the Facebook search bar draws my eye.

I type my schoolmate’s name, the one who lived on 180th. I hit enter.

No results. Except, in a tangentially related post, I find: “That guy murdered my boyfriend’s dad,” on a death row execution tracker group. “If they don’t kill him, I will.” “Why is he still breathing” another person asked.

I type in the baby girl’s name.

She is, of course, a woman. About as old now as her mother was when she was victimized, as old as her dad when he was murdered. There’s a photo of her on a mission trip. There she is smiling with friends. There she is skydiving.

I have no desire to contact these people. They’ve been through more than I can imagine. They don’t know me, and I don’t know them. I just know what happened to them, all those years ago, and that I thought about them every single day as I walked past their home; afraid but blessedly, if tenuously, safe. They only ever got to feel afraid. I am a background character in their story, an uncredited extra. Whatever they had to do to cross that street, there’s no way I, a stranger who has filed away the memory of their pain as an addendum to my own story, there’s no way I would ever ask them to go back.

Neither will I ever forget them, or that horror that happened to them, something so awful that 30 years later, a child they didn’t know would spend hours reading through newspaper clippings, looking for answers.

I close Facebook.

The internet window is still open.

One last search before bed.

PHOTOS: Bay Area inmates On Death Row At San Quentin State Prison

CBS News, March 13, 2019

California is closing San Quentin’s death row. This is its gruesome history

LA Times, Feb 8, 2022

And then. A photo.

My name is Randy Garcia. I have been locked up since May - 1993. I was 22.

I have been on the row since 1995. Truly - the death penalty is a poor

mans sentence. But responsibility must be taken. I will answer ALL letters.

It’s 11:30 by the time we’re closing up the house for the night. My kids have been in bed for well over an hour, and all is quiet. The 9-year-old didn’t come out tonight.

My husband is in our closet picking his clothes for the next day while I quietly open the door to my little boys’ room. I tiptoe over and peek through the slats of the top bunk. My son is asleep. Our talk must’ve helped. I gently close the door and go back to the living room, lock the front deadbolt, pick up the laptop.

The cursor on my screen blinks, waiting, waiting, waiting.

My name is Randy Garcia. … I will answer ALL letters.

I close the screen and go to bed.

Erin, as I read this powerful and beautiful essay, I kept feeling like I was reading something from The Best American Essays. The way you link our sweet little childhood fears to the real evils and dangers, both human and chemical, that lurk all around us, was just astonishing. I kept thinking, “She’s right! Of course we were terrified as children; the world is terrifying.”

And as a mom, I was particularly terrified by that route you walked to school every day. I grew up in a working-class, rural community, and your essay made me feel very lucky.

This is a gorgeous, heartfelt, beautifully-structured piece of writing. Sorry, I feel like I sound like your English teacher saying that, but the flow between events in this is really affecting.